I am 12 years old, my Dukes hat ringed in the chalk white that comes only after a Summer spent sweating. It’s sweltering heat, and the air smells like a rainfall a few miles off, just beginning to creep over the Sandia Mountains that loom like sentinels in shadow in the distance beyond the centerfield fence. The stadium lights have been turned on, but aren’t needed, not yet, there’s enough daylight to stretch through the first few innings, but old lights take awhile to heat up, to truly shine.

Five or six thousand people will find their seats before the first pitch, and already there are enough to make the whole place hum. There’s a din to a crowd, a murmur of half syllables and broken words, staccato laughter, whistles that rise above the noise to signal someone, somewhere, to come closer. I’m alone on the left-field foul line, black baseball mitt on my left hand and a red sweatband on my right wrist, I’m in shorts and busted Nikes, and I feel like I am 32 feet tall.

Our summers looked different than those of my Mom and sisters, they always had. The days started the same, early breakfast, time at the communal pool always positioned in the centermost point of a some sprawling apartment complex in some city that wasn’t home, but would be for a time. Then came an 11am lunch, as this is where our days diverged, they and we. In truth, I’m not quite sure what they filled their days with, this a mystery that I’ve never sought to solve, but ours, ours were with the Boys of Summer, and had been that way since my memories knew to form, and I knew to remember them. We’d go to the baseball stadium, “the park,” we called it, every day by about noon, as my dad was a coach from the time I was born, and coaches get there before the players. This, an unspoken rule, one of dozens that make the National Pastime what it is, what it’s always been. From the moment we walked through the clubhouse door, locked but for players and coaches, a subsequent divergence took place, this time me from him, as I was trusted to occupy myself, to behave myself, to find my way as a part of the team, in my own way. It was this way from so nearly the start, I, the little kid in the #3 jersey and a mitt four sizes too big, shagging fly balls during batting practice, chasing down the homeruns on the backside of the outfield fence, spitting sunflower seeds onto the red dirt of the warning track, chewing bubblegum, drinking gatorade out of tiny green cups.

Baseball, as much as my Father, raised me.

It was a ritual we shared, my Dad and I, before every home game, and it was my favorite part of every single day. After batting practice (BP for those who were also raised by this game, be it as players or fans, coaches or boosters with their long plastic trumpet horns), after Infield where ground balls were hit with scorching ferocity and double plays simulated, after the pristine red dirt was once again dragged by two men on little four-wheeler ATVs, when all was quiet and the anticipation of the home team running out on to the field, it was our time, my Dad and I.

He’d tell me to run out to centerfield, and he’d bring a bucket of balls with him in one hand, a Fungo in the other. Fly ball after fly ball he’d hit me, somehow placing them precisely where he wanted them to truly challenge me, and I would have to run them all down. All this, with a stadium rapidly filling with Albuquerque Duke fans waiting for their game to start, all this, with thousands of eyes on some string-bean twelve-year-old in clay-stained Nikes diving onto that perfect green grass.

I remember the cheers when I made some unbelievable shoestring catch on a fly ball I had no business getting to, the whole stadium erupting in applause and whistles, as pre-game entertainment consisted of me, and me alone. I remember the deep and resounding boos when I’d drop an easy one, and maybe, if I’m honest, I remember those with just a bit more clarity. Twenty minutes that felt like twenty seconds, that now, standing here and writing this, feels like twenty thousand years ago.

It’s a swirl now, as memories tend to coalesce into one shimmering mass after a time, its colors more than most things that do the shining. It’s the red clay dirt, the green of the grass, it’s the black volcanic rock just beyond the outfield fence. It’s the deep grey blue of monsoon storm clouds that rolled in every day like clockwork, it’s the white-yellow crack of lightning that hid behind that charcoal curtain. It’s the tan of my young skin that I brought back to Montana with me each year, it’s the white of the brand new Pacific Coast League baseball, the deep brown of pine tar smeared halfway up a player’s favorite bat, the sandy brown of the adobe buildings halfway between the Sandias and where I stood. More than anything though, it’s the white of my Dad’s jersey, the bright red 33 on the back, it’s the deep sun soaked toffee of his skin from so many years as a Boy of Summer himself, it’s the white of his teeth when he smiled at one of my catches.

When reduced down, when all things are placed into the great crockpot of time, when simmered long enough, that’s all that really remains, just his colors, just mine, and nothing else. It’s him, and it’s me, alone on that field, it’s fly balls on a Summer night, pastel colors bleeding across a sky I don’t even bother stopping to truly appreciate, as another catch needs to be made. It’s us, day after day, year after year, some home game against some random team filled with thirty young men trying their damndest to get a call up to the Big Show, and not a damn thing matters except for those twenty minutes.

It’s us, above the din of it all, alone, in a blur of everything else that I remember, it’s us, the center of all things, sharing what we’ve always shared. Baseball, the glue, the foundation that it all rests upon. I wish now, I could reach back through the deep fog of time and shake that little twelve year old, grab him, whisper soft in his ear to just slow down, just soak every single detail in, just hold it like a treasured thing some place untouchable by time or life, loss or ache. Hold it, and never let it go.

I stand here, writing this, all these details I didn’t know I still knew, and I realize, maybe, just maybe, I already did reach back, parted that veil of years, and whispered what I said I wish I could. After all,

I remember everything.

Happy Father’s Day Daddy-O. Thank you for every single moment of my life.

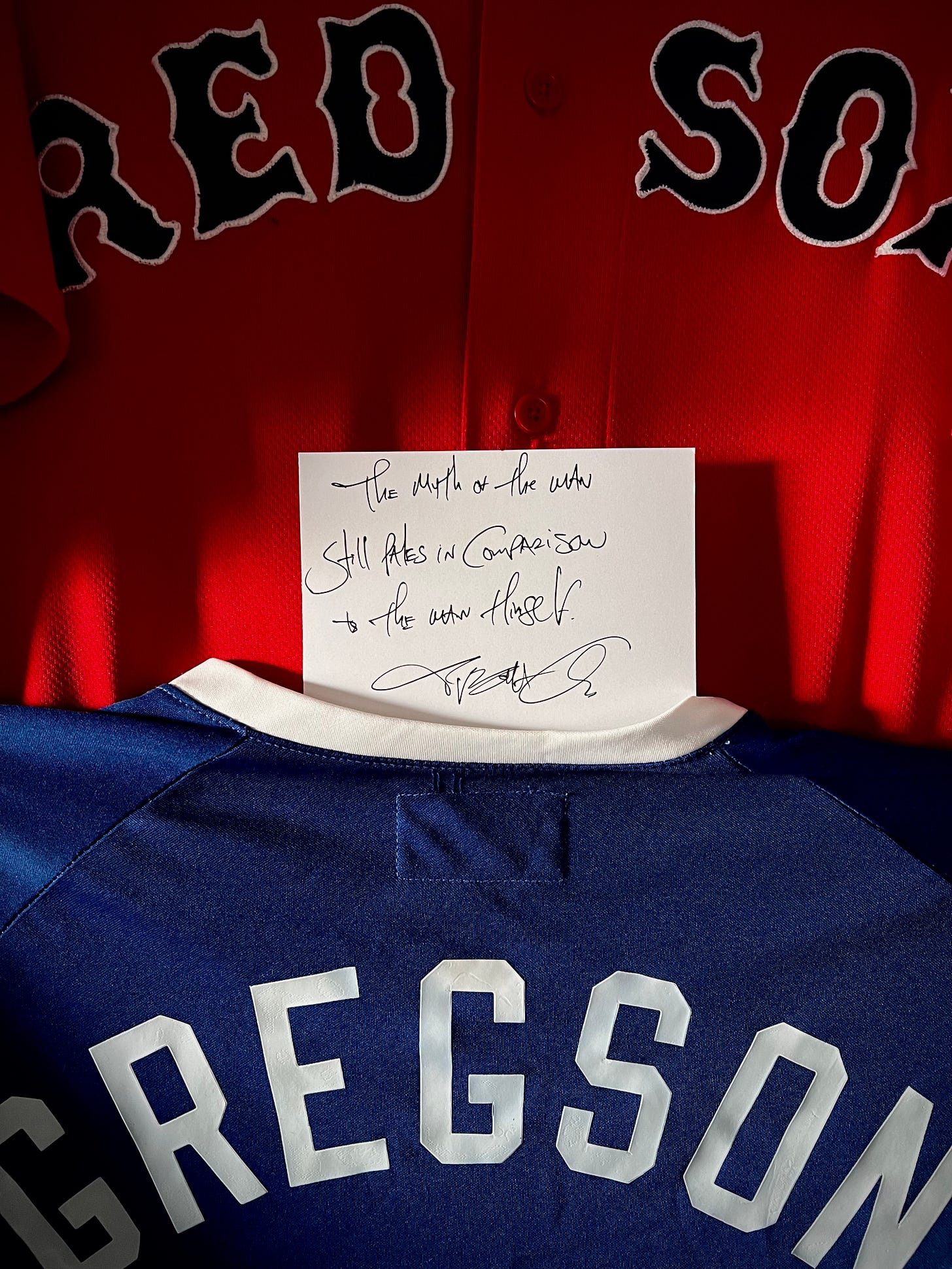

The myth of the man

still pales in comparison

to the man himself.

Share this post