This is a bit of a rant, and will probably ruffle some feathers, but I only know to be honest, and in the pursuit of that, I must say: I’ve lost count at this point. Somewhere around 100? Maybe 200? I had to stop counting how many different people from different random publications, universities, high schools, blogs, or podcasts approached me wanting an interview about “Instapoetry” and how I felt about my role in its rise to popularity. They asked, over and over again, if I considered myself an “Instapoet” or if I found that term offensive, if I wondered myself about what the term meant. I always answered with kindness, I always did my very best to not seem bored or irritated, and I always gave the same answers. Look up any number of the interviews and you’ll see a common thread running through them all, and that thread is this:

I am a poet, that happens to use Instagram, and social media, to share some of my work. I am a poet, who has written since he was 11 years old for one reason, and one reason only: To get out the aching noise inside. That is it, that is all. All the rest is semantics.

It seems to me that there’s long been divide between POETRY and “poetry” and it’s an unfortunate one, in my humblest opinion. There is an invisible line, a border that you can’t quite see or pick out, but know it’s there. It hums, as though electrified, and it wraps an entire community in a seemingly impenetrable shield. This is Poetry, and I do not blame—not always at least—the poets that live inside this gated community, but I do feel sadness for the role that so many outside of it play in erecting that buzzing wire at its perimeter.

Only those allowed inside the gates, beyond that hallowed borderland, are allowed to be called Poets, only their work allowed to be called Poetry. The more opaque the words written, the more seemingly disjointed or jarring, the more aimed entirely at the demonstration of obscure words that most often fail to appear in normal nomenclature, the higher the level of praise. To be blunt, I have found that so much of the capital P POETRY that gets published, that gets praised, that gets passed around and yes, paid for, is opaque to the point of not being relatable, it’s intentionally this way, and meaning is assigned to what could quite possibly have very little at all. It’s said in a way that makes people snap their fingers at fancy readings because, quite possibly, collectively, no one actually understands what the fuck is being said.

I have seen this line drawn in front of me many, many times since I began writing, I have seen it most profoundly since my first book of poetry, Chasers of the Light, became a National best-seller on a variety of lists. It sold enough copies to be 4th on the New York Times Best-sellers list too, but due to weirdnesses and payolas I don’t even need to get into, they decided to not place it there. I remember talking to my publisher at the time, to my agent, and hearing that they didn’t know where to put it, they didn’t know what to call it. Was it poetry? Was it something new? The New York Times, ironically, then came to a book signing in the Upper East Side in New York and wrote an article about it called “Web Poets’ Society: New Breed Succeeds In Taking Verse Viral,” that I believe was the very first time the word “Instapoet” was launched into the world. *I could be wrong, it could have come before, but I think this is the first I saw it published.* Here’s how they said it:

“The rapid rise of Instapoets probably will not shake up the literary establishment, and their writing is unlikely to impress literary critics or purists who might sneer at conflating clicks with artistic quality. But they could reshape the lingering perception of poetry as a creative medium in decline.”

Ahh there’s the rub. Because I wasn’t part of the literary establishment, my writing “is unlikely to impress literary critics or purists who might sneer at conflating clicks with artistic quality.” And you know what, that’s fine. That’s more than fine, as I’ve always associated so much more intimately with the riff raff than the high society. For me, it’s never been about the triple letter scores of the words you choose, the paper stock your books are printed on, the indecipherability of what you’re actually trying to say. It’s not about what some professor in some school discerns from the words you’ve written, not about the awards or even the number of books you’ve sold. Poetry, to me, as I have said time and time again, is much simpler, it’s “Taking an ache, and making it sing.” If someone understands the lyrics to that haunting song you’re singing, if someone feels understood by the words you’ve written, THIS to me, is poetry.

I understand the idea that poetry is an elevation, and should be. The problem I have, is I don’t always believe it needs to be an elevation of only language. Shouldn’t it also be about the elevation of emotion, of the experience, of that aching? Isn’t it poetry, taking some random bit of mundanity that plagues the existence of every person on this planet, and elevating it to a point of a slight gasp and punch to the gut that says, “YES, THIS, EXACTLY THIS!?” Isn’t it often harder to say something that people relate to so deeply that they feel seen, often for the first time, to condense down a thought from big to little, to make the indescribable actually digestible and to make sense of the senselessness that can surround us?

Isn’t that poetry too? Isn’t it ALL poetry?

Part of the problem is in the industry itself, as poetry traditionally has never sold a great number of books. The NYT article was quick to almost use my book sales against me, comparing my initial print run to that of National Book Award winner Luise Glück and “putting it into perspective” by showing my run at 100,000 copies more. Who cares? Isn’t all this just creating a further divide between people all doing the same thing, all trying to achieve the same end? Aren’t we all just trying to clear out the noise and nonsense that lives in our own minds, aren’t we all just trying to make sense of the world we see with the words that feel right to us?

I love reading poetry, I love a lot of poets, from the natural rhythm and stunning feel of Ada Limón, to the unbelievable activism, lyricism, and ferocity of

, to the raw honesty and beauty of , to , to , to Mag Gabbert, to Liz Berry with her accent making her words music, to my fellow Autistic slam poet brother-from-another-mother , though he too has been called Instapoet, has been reduced to something less because he chooses to share his work on social media, too.Don’t we all, now? Everyone I mentioned above shares work on social media, connects with the people who love their words everywhere from Tik Tok to Instagram, Facebook to YouTube, and what a beautiful thing that is. To create a place for intimacy between those who write the words and those who love the words, what a beautiful thing.

In the end, why does it matter, and why does that electric horse wire exist at all? Isn’t there room in the word for all of us? Isn’t Poetry big enough to house a million voices from a million places? Aren’t we all suffering? Don’t we all deserve to voice our words, no matter how we choose to share them, what words we use to do so?

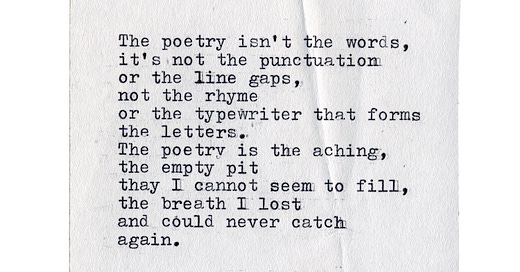

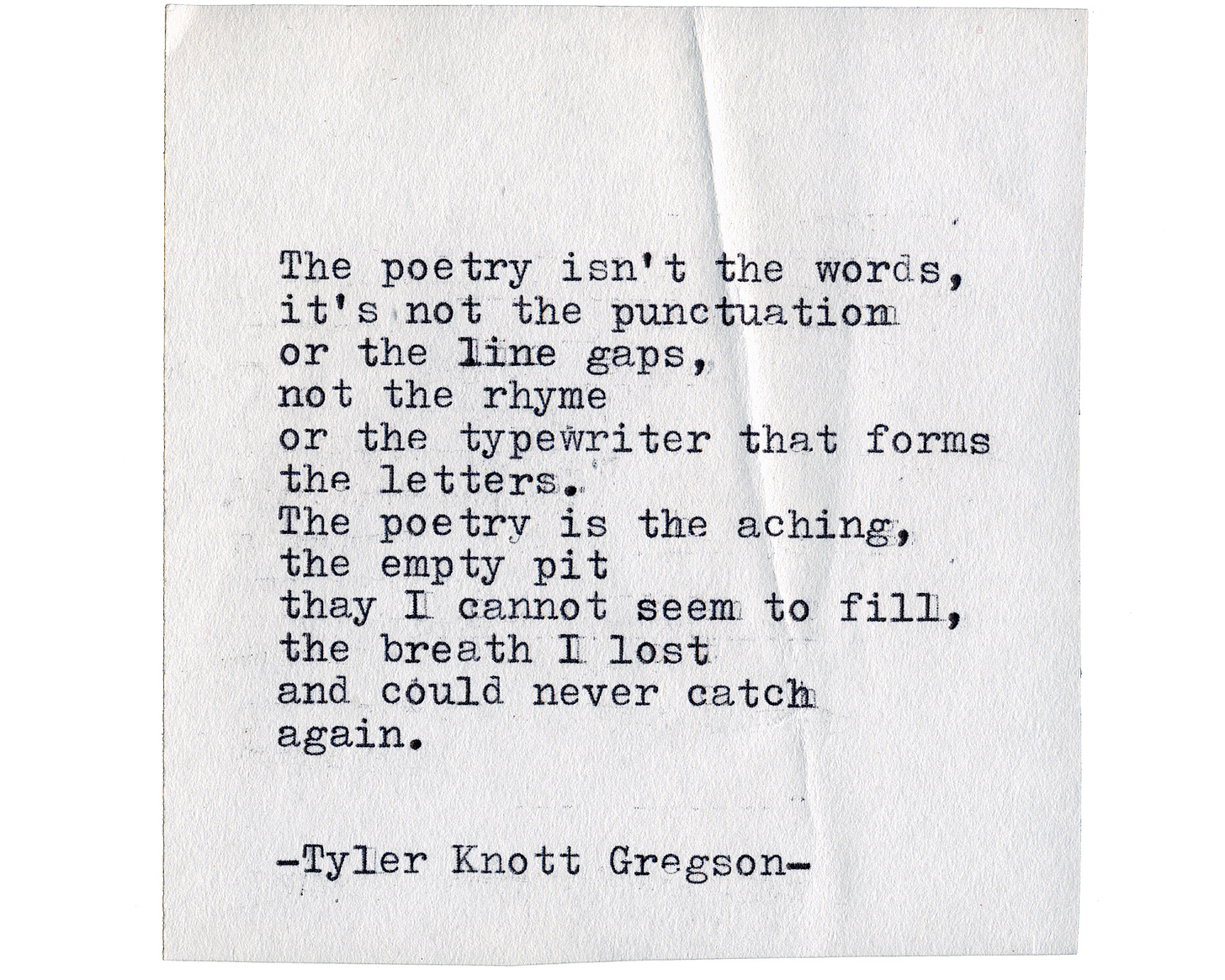

As my poem, or instapoem, or whatever you wish to call it, above says,

The poetry is the aching, the empty pit I cannot seem to fill

and it’s always been this.

Call it what you wish, lock me outside the gates if you need to, but I’ll keep writing, and all that matters is once it’s written, I no longer have to carry it. It’s no longer a burden I must bear. If anyone, anywhere, reads it and feels that whoosh of air from their lungs as they finally feel seen, finally feel understood, even better. Even better.

That’s poetry, to me.

Keep your capital P, I’ll stay lowercase forever.

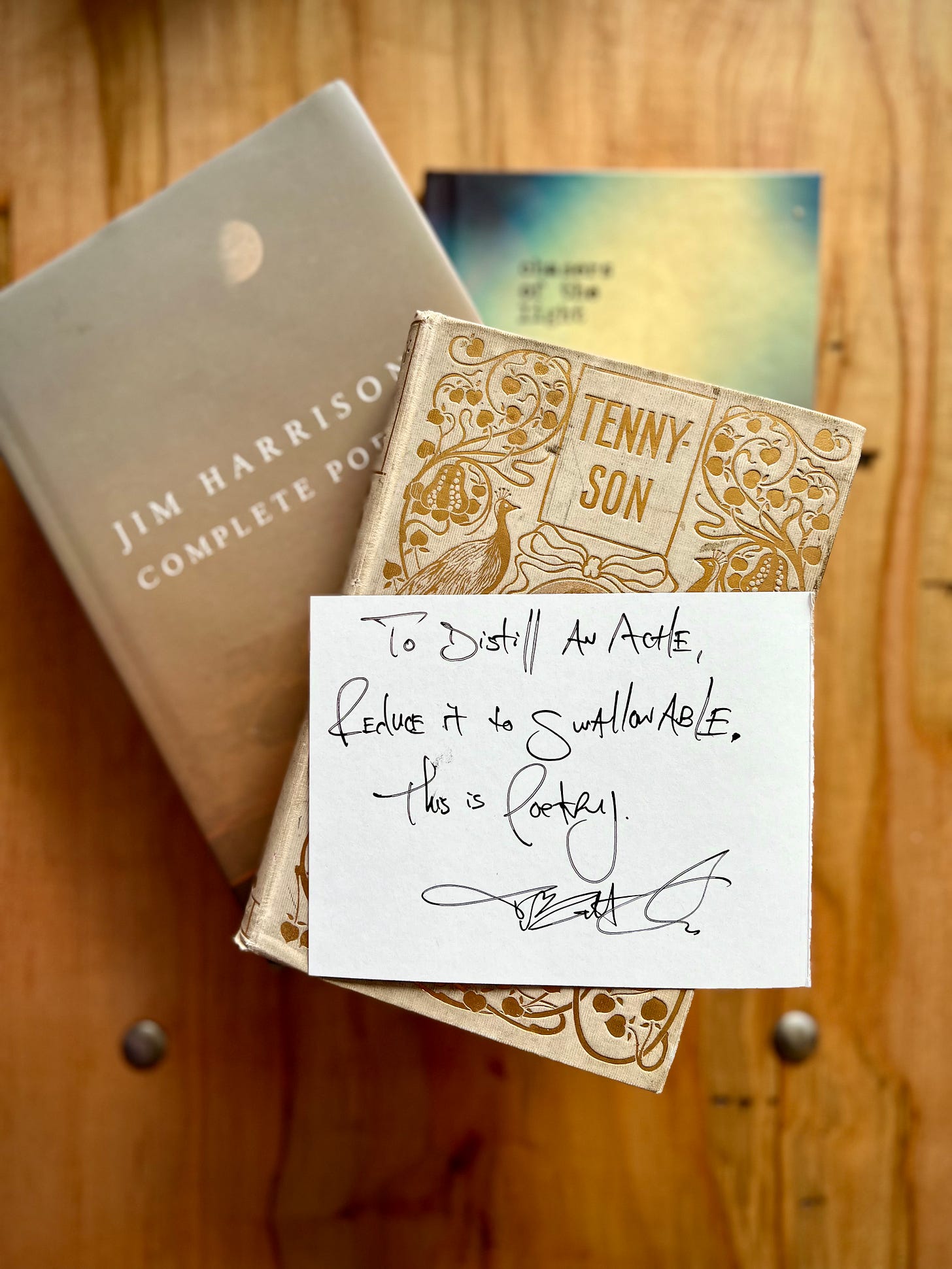

To distill an ache,

reduce it to swallowable.

This is poetry.

I went to a lecture recently by my state’s Poet Laureate where he talked about this exact topic. More specifically, he spoke on how the Lost Generation is the group of writers that shifted poetry from being something commonplace and enjoyed by all to being something more distinct and elitist. I’d never known much about the history of poetry, so it was fascinating to hear its evolution.

At the end of his lecture, I asked what he thought about “Instapoets” and the hate they often get for not being “real poets”. His response was that anything that brings someone to appreciate poetry is valuable and worth appreciating.

I have many artistic friends. Designers, musicians, writers, you name it. And I often spend time reflecting on the complete randomness that some people who share their talent become adored by society and others are never discovered. Is my friend’s song any less transformative, just because it was only heard by a group of 10 instead of 10,000? I wouldn’t say so.

This is becoming an essay, but all of this to say that I think we should stop looking to what society deems as acceptable art and just start seeking out things that touch our hearts. Honestly, more power to us all if we find it in the hidden corners where others don’t want to shine a light.

randomness. yes. what happened to the value of front porch music with neighbors and singing while you do your household chores? Yes to seeking out what touches our hearts!!

I FULLY AGREE. Your closing statement is absolutely perfect. As usual.

Yes, and while it’s not necessarily to validate to us, we understand the need, the ache! In my fantasy to rant, I see masses walking down Main Street with signs like:

I am a poet

I may not be your poet

With or without rhyme

YESSS MAKE THE SIGNS.

Yes, this could be quite controversial to some/ “highbrows”. It could be said for all of the arts. For example, Fine Art vs. art: I love the AI art of Kaoru Yamada but it gets so many knickers in a knot when her work is posted in a FB painting group: some argue that it’s NOT painting or even art yet her work gets so many positive comments as well. Like her, your poetry touches people in a real, understandable way. When I showed some of my poetry to my high school English teacher, he said he liked it, “but have you read T.S. Eliot?” I dutifully read some and once I read notes in order to decipher the meaning behind it, I recognized it as profound but not accessible nor that enjoyable (someone, somewhere, is gasping at me for saying that). Literature vs. literature: sure Moby Dick is a “Classic” but you won’t find anyone reading it on the beach this summer. Beethoven’s music is far infinitely more complex etc. than most music today but none of his pieces are in my playlists. I couldn’t open the NY Times article without opting for a ‘free’ subscription so I couldn’t see when it was written and when they coined the term. It seems to me that nowadays any wise artist, musician, writer needs to get their work out on social media- I happily discover so many in this way. I actually see their words as a backhanded compliment to you- that your work has re-invigorated an interest in poetry and how we conceptualize what poetry is. I read the quote from the article as a criticism of the critics and purists who would “sneer” at poetry vs. Poetry. You just keep doing what you’re doing- and we will keep showing up here, and wherever we can access your words.

Oops- switch the order of “far” and “infinitely”. But then, I’m just a writer and not a Writer. 😜

Here's to the lowercase, whether it's poet or writer, I prefer it so. Thank you for you.

I'm a millennial, which colors my experience, but I love the insta poets. I have read enough "true poetry" that did nothing to change me. I want poetry that pierces my heart, hits the longing, or uncovers unknowns that leave me minutely different for reading it. With most insta poetry I find a different level of connection, comraderie, a yearning in those pieces. They speak to shared experiences with an accessibility that I crave. I want the poetry that burns me; the way that I discover it does not change its value.

Instapoetry is not bad for poetry. It might be bad for the institution of poetry but that is not something that I care about at all. If people find something they love let them love it and if they find something that speaks to their soul let them have it. We all need moments of small sparkle.

Elise, hearing this from a different generation is magic, and means more than you know. You're amazing and I love ya.

Wait, did you just call me Riff Raff? LOL. But seriously though. THANK YOU for this post, for telling this story, you are educating me about all this. I did not encounter you thru Insta bc I don't have any social media cx FB, and only that to access some things I care about or can't find locally. (I never post anything). So you have never been "Insta Poet" to me. AND, I immediately connected with your life calling of being present with/making something beautiful and useful out of pain. (And I desperately NEED examples of this in my life). Which to me says integrity. You have integrity as an artist. However you put it out into the world is your choice, you're the poet. AND, when you are true to your art, that effect ripples out into the world and THAT is a benefit to all poets, in their gazillions (thankfully) of manifestations. Let the world spin things as it will, us riff raff know who you are. (smile)

If you're here, you're Riff Raff, and that's the highest praise of all time. :) Thank YOU for being here, and for being open to all the random shit I post. Thank you for these kind words, for the boost, for the reminder that it all matters.

To speak less and say more

is an art of the highest order

To be easily understood

is the science of mastery

…Or so I heard, and so believe, let it be written, spoken, sung, on page and screen. For I can’t be the one of such words, but for the voiceless –sing.

But, you just did

We're all poetry in Motion.

And, you wear it so well.

Oooh, I love this Megan, so very much.

lower case for always

It probably comes as little surprise that I am one of those bright sparks. That the origin story? The very missed Richard Gill let the chinadoll sing 'little boy blue' with perfect pitch at the Baby Proms with the SSO. I was three or four.

What happens when you submit a subgenre of crime fiction to the Canon of English Literature, and if gets accepted? At 22. When you also ran the world; closed the gap; did a grade 8 piano exam; attended as many 21sts as you could; showed up for your kin; and loved the bright eyed boy who said "this year is yours. I'll keep it running. You take care of everyone else, I'll take care of you".

You need to be loyal to the things that fill your cup.

You know who cared for me? Before the Legend of the class of 04? TKG. He had a typewriter & his words were a universe of pools of sorrow. And, the waves? The waves were euphoric.

He outlasted Kurt Halsey. Outwitted John Mayer. Was the safe harbour that Matt Nathanson is sometimes not because he is red cordial & we are the runaways lighting the night.

The extroverted introverts; the Playmakers who do not need applause to live.

Here. Here is our home.

If there is not room for everyone?

I do not want to live there.

It is abhorrently hateful & a real chocolate teapot move to posit you as the Swifty of Poetry.

It says more about them, and their gatekeepers & the capitalist signs that they wear as armours of grandeur.

It was never about you.

Let them race to the bottom.

(Yeah, JSchool for Masters made me an adamantium weapon. I know how the sausage is made. They clickbait you & then they have the audacity to want to hit you over the head again with a newspaper? No.)

I ABSOLUTELY LOVE this line: "The extroverted introverts; the Playmakers who do not need applause to live."

I agree! Tyler your poetry was really the gateway for me if I'm being completely honest. I didn't connect much with what I had read before. A few poems here and there, but yours consistently made me feel things and I will forever be grateful!!!

I'm a gateway drug! I MADE IT!

Indeed! 🤣 I have so many poetry books now haha

I was late to the game, only finding you last fall, so I had no idea that InstaPoetry was even a thing! But I did find you on Instagram because I followed the hashtag of a singer I had also just discovered (seriously you guys are the best twofer ever!). Because that is what we do now. We manipulate the algorithms to show us what we want to see and fine tune what we are fed in our feeds (how weird that we have normalized that term no?).

I wonder how many Poets looked down their noses when we first invented the printing press at those who chose to release their work to the masses? Or when radio was invented and the audio version became a thing. And then television; the Internet and its World Wide Web of communication possibilities. Heck, cave poets who had the audacity to mark their musings on the wall instead of just passing them on orally were also probably mocked with a neandrathalic side eye. There is always pushback when we evolve our method of communication and it is usually because that evolution allows us to reach more people with greater ease which causes a greater impact and weight to our words.

So blaze that trail and shine your light! Inspire others and lead the way! And when you're an old poetic fart, don't look down on the poets who project their image via hologram into the chip we all have inserted in our eyeballs, or whatever way we are compelled to share by that stage of the game!

I'm so glad you found me at all, it's getting harder and harder, a sea of lookalikes make you vanish anymore. This is such a beautiful comment, and so f'ing well said. As usual.

Yes yes yes. I struggle so much with to share my poetry online or not. If I am a poet or not. You are right though. Once it is written and shared, I no longer have to carry it alone. I'm so thankful for you and your poetry. And your support.

SHARE IT! The world needs it. Truly.

"Keep your capital P, I'll stay lowercase forever." Mic drop!!

First and foremost, I agree with everything you said. Gatekeeping for anything is so dumb. Whether it's creation/art, life experiences, anything... Because we are, all of us, unique. Our experiences, perspectives, it's all different. So even if we do the same thing, or make the same thing, it is still going to be different because WE are different.

Also... There is some HUGE irony in getting shit on for having work posted on social media.... Because to get a book deal these days, to get a publishing house to bother with anyone's work, they need to have a substantial instagram following!! To do a huge chunk of the legwork of promoting their upcoming book!!! So, if writers want to be successful they'd better have a great social media following but if you are successful at posting on socials and getting that online recognition, then you're not a "real" poet/writer?!!! What in the Sam Dickens is that bullshit?!!!

Plus, even outside of writing and poetry.... Social media is used by basically any kind of professional or business owner who wants a fast and free way to advertise their goods with a potential to reach a huuuge number of people. Sooooo basically everyone does it. So why shit on the artists who use it, and say that illegitimizes (not a word) their work?!!

Ughhhh

I will join you in this rant forever.

You are the poet-est (also not a word) of all posts. I love that you post on social media because that's how I found your work -- a Pinterest post that I saw, when I was a bored college student scrolly-scrolling in class instead of paying attention (whoops) in 2012, and I instantly looked up as much of your stuff as I could find. It changed my life. It floated me through some of the darkest times of my life. So if that isn't poetry, then nothing is.

Thank YOU for picking up the mic I dropped! And I fully agree, gatekeeping stops so much beauty from entering this world. And, I have a new Signal Fire coming about precisely your 2nd paragraph. Welcome to the rant, you did a much better job than I did at expressing it hahaha.

Not better!! #teamwork

I have never thought of you as less than a capital P because when I read your words I feel seen. I feel a rush of emotions. It’s a beautiful connection. There are many poets I don’t understand and I often wondered how they became famous. I feel like I need a manual of understanding to relate to what they have to say.

Thank you for your words, your silliness, your energy. It’s brings light to so many. I have learned more about poetry from you than anyone else. #grateful

Amber, thank you so much. Capital P or lowercase p, matters not, if it reaches people like you, it's all worth it.

I, as someone who probably would never have found your work (or you) sitting on top of some bookcase shelf somewhere…, appreciate you sharing your poetry, works, art, experience & existence on a more “social”, “untraditional” and maybe “unacceptable” platform. I’ll take lowercase forever. ❤️

Welcome to the lowercase, I love ya, and I am so thankful for you.

Poetry, when I wrote it, has always been about releasing what I held too tightly inside. High school and my days in college were peak times, expressing a heart loneliness as I was always overlooked as a date because "i was wife material" [as it was explained to me by a table of men.]

But the pinnacle of my writing, poetry and prose, came during my years of untreated, and trying to find the right treatment for, depression. It was a long haul. I wrote small tidbits of 'stories' called "Stories of She". She who struggled but rose from the fire, not as a Phoenix, but as something claiming sovereignty, her new place in the world of chaos and beyond.

And yes, I shared it on social media. WordPress [Reikiflower Daily Muse] mostly and a page on Facebook named "Chaotic Whirlpools. I don't post there as much anymore, but if you scroll back to the archives ... there are some gems there . Honest speak of my recovery and what depression is to me. It's all out there. It helped me heal. All the writing was the 'best' thing about my depression. The right meds have stolen it from me mostly.

All this to say, I understand as I am one of the 'Instapoets' [although having never posted an of it on Instagram.] For me, kind of like a 'published' journal.

I'm so glad I found you so long ago ... not even sure how I found you, but it was online.

Stories of She sounds breathtaking. I'll dive back and check them out. I'm so glad you found me, too. So glad you call this place another home.

THIS. I majored in English lit in university, and it often frustrated me that so much of the poetry we studied was indecipherable to the point where I couldn't glean any emotion from it. Your poetry has inspired me to feel more comfortable writing my own poetry, and I can't tell you how much I appreciate it. Thank you, thank you, thank you for your words, which always leave me feeling moved and inspired to explore the world and my thoughts and emotions from a different perspective.

Thank YOU for this, SO much for this. To hear it from someone who studied it, who sat through it, who had to try so hard to understand what quite possibly was not even written TO be understood, means even more. You're magic, and I'm so happy you're here.

🤗

I couldn’t agree with you more. I am a poet and have often criticized my own writing for not being hard to interpret or using the fanciest of words. If I’m being honest though, I much prefer the simplicity, the raw feelings spoke in a direct way. Words that reach inside you and stir something, anything. I love your writing so much and I see nothing wrong with sharing it in all the ways. Art is art and poetry is definitely that.

I’ve been a fan for yeeeears & you’ve made me feel seen & understood all along the way. In some ways, we’ve grown up together! Thank you to my favorite poet. 🫶

The first word that popped into my head after reading this is simply…FUCK. You could not have spoken this truth any better. What a shame that we judge and categorize and reduce artists the way we do. That only some are worthy. But also like you said, who cares? We know what matters. We can feel the ache and its release when we hit the page. I love love love how you talk about what poetry is. The poem at the top of this email hit me so deeply today like it is rooted in my bones. I cannot ever express the amount to which your poetry has changed my life. You have given words to so many of the things I feel and ALSO created a community around them. If that’s not an accomplished life, I don’t know what is.